*Credit: Baylor University's online doctorate of education program

Human trafficking may seem like an unusual topic to bring up with a child. The subject matter can be frightening, particularly for younger children, and educators and parents may be uncomfortable starting the conversation.

Human trafficking may seem like an unusual topic to bring up with a child. The subject matter can be frightening, particularly for younger children, and educators and parents may be uncomfortable starting the conversation.

But recent data from the National Human Trafficking Hotline, External link a phone number that victims can call for help, suggests that human trafficking is a relevant topic especially for children.

In 2017, the hotline documented the cases of more than 10,000 victims of human trafficking in the United States. While about 60 percent of these survivors were minors at the time of being trafficked, only about a third of those who called the line were minors, which may mean that many young victims are unable to find necessary help.1

Certain groups of children are particularly vulnerable to being trafficked, says Lakia M. Scott, Ph.D., External link an assistant professor at Baylor University’s School of Education. Those who are most at risk include children from low socioeconomic backgrounds or single-parent homes, those without homes, and those who lack access to education.

According to Dr. Scott, children’s lack of awareness about this global epidemic is to their own detriment. Educators and parents must be unafraid to begin having these conversations with their students and children now.

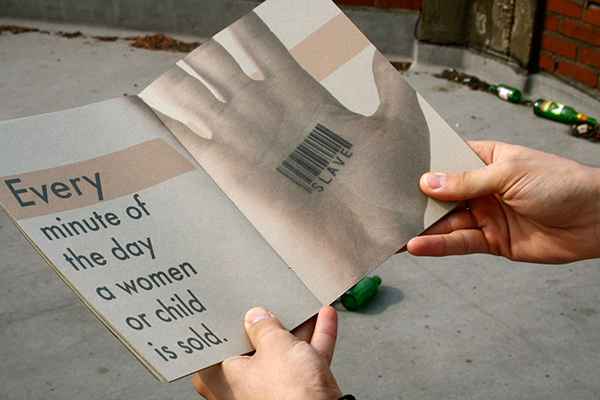

Human trafficking is a form of modern-day slavery and is defined by the U.S. Department of State as “the act of recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, or obtaining a person for compelled labor or commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud, or coercion.2

As an educator or parent, you can prepare to start the conversation by making sure your own understanding of human trafficking is accurate and complete.

Below, Dr. Scott breaks down common misconceptions about trafficking.

Children may not be aware that multiple forms of trafficking exist:

They may also not understand how the need for money factors heavily into why people are trafficked. By making children aware of the different forms of trafficking and the economics of each, adults better prepare them to recognize and avoid potentially dangerous scenarios.

According to data from the National Human Trafficking Hotline, these venues and industries are where trafficking most frequently occurred in 2017:

However, labor trafficking also occurs in places we might not expect:

Human trafficking can happen with little or no movement at all. People can be trafficked within their hometowns, and children can be trafficked while living under their parents’ roofs.

People may picture third-world countries when they think of human trafficking, but it does indeed happen in developed nations. Since December 2007, the National Human Trafficking Hotline has documented more than 40,000 human trafficking cases in the United States.4 Texas alone saw 455 cases reported in 2018.5

Teachers may struggle to find a curriculum that explores human trafficking and also meets district, state, and common core educational standards.

For this reason, Baylor University’s online doctorate of education program asked Dr. Scott for advice on how educators and parents can weave the topics into daily discussions and lesson plans—and keep the dialogue transparent and open.

Below, you’ll find recommendations for beginning these conversations with children, adolescents, and teenagers at every stage.

Children between ages 2 and 6 are probably not ready for explicit conversations about human trafficking. But educators and parents can begin helping children develop an understanding of their own inherent worth and the value of every human life.

Children at this stage begin learning to care for themselves. They start brushing their own teeth, dressing themselves, and using the bathroom on their own. Use this time as an opportunity to help children understand that we should care for our bodies and treat them with respect. Other people’s bodies deserve our respect, too.

Explain that our bodies should never be used to get something we want—even if someone offers a prize, candy, or a toy.

Make sure children know they always have the right to ask for personal space. They should respect other people’s personal space as well. If another child or adult makes them feel uncomfortable, then they should tell an adult they trust as soon as possible.

When a child witnesses something unfair happening at school, talk about what happened and address their feelings. Reiterate that fairness is one of our core values and should never be compromised.

You might say, “It’s not fair that John took Miguel’s toy truck without asking. And it’s okay for you to feel mad or sad about it.”

Gently help children understand that sometimes life is unfair, but this does not make cruelty and unkindness okay.

As children begin to socialize outside their families, they will start to pick up on the different expectations of girls and boys and of women and men. Help children learn to recognize stereotypes and understand how they affect our relationships and social behaviors. Opening this conversation can help prepare young children to consider more serious questions about gender identity later on.

“Mommy likes to cook, but that doesn’t mean she has to cook.”

“Daddy works hard to make sure our family is comfortable and safe. But even if he loses his job, he is still a good dad.”

“If Susan doesn’t want to give James a hug, she does not have to just because she’s a girl.”

Children between ages 7 and 12 have more world experience, abstract thinking skills, and abilities to better express themselves than younger children. They are also more likely to be exposed to upsetting news and online content that is violent or inappropriate. Provide a safe place for kids in this age group to discuss these things and affirm them for coming to you with questions.

Between ages 7 and 12, children begin to understand work as something adults do during the week in exchange for money, which helps them pay for things their families need: food, school supplies, clothes, and their homes.

When children come to visit you at work, or when they ask about your job, consider introducing the concept of forced labor. Explain that many people in the world don’t get to choose their jobs. Many times they are forced to work without being paid fairly, and they may even work in unsafe conditions.

Older children may begin noticing members of the armed services in their communities. At school, they will start learning about the military in history classes. As these topics come up in conversation, introduce the practice of child soldiering.

Explain that some nations have unfair leaders who force children to serve in the military. These children don’t get to go to school, play, read books, or rest.

If the children you parent or teach receive an allowance, start teaching them about fair compensation. You could open the conversation with, “You’re a kid, and you get 5 dollars each week. But do you think it’s fair for an adult to earn 5 dollars per week?”

Explain that some people work for very little money. Highlight the importance of being diligent and doing research about the clothes and food we consume in order to make sure the people behind them are being treated fairly.

Adolescents are better prepared to discuss complex issues but may be less willing to open up to an educator or parent, especially about sensitive topics. Broach the subject anyway, knowing that the information you share may keep your children safe and make them advocates for fair labor practices and healthy relationships.

As they begin dating, adolescents need to know that their bodies are not commodities for others to use for pleasure or money. Emphasize that sexual relationships should always be explicitly consensual, and we should never have to exchange sexual acts for safety.

Adolescents may not comprehend the economic side of trafficking, particularly if their only understanding of human trafficking is sex trafficking. As they learn about economics and international trade, educators and parents can open discussions about bonded labor and involuntary domestic servitude.

Adolescents may begin working or have friends who hold jobs while going to school. As they start managing money, teach them how to manage their finances, including reading a paycheck, creating a weekly budget, and saving and giving money. Good habits with money can help adolescents avoid desperate and potentially dangerous financial situations in the future.

When your children ask questions that you don’t know how to address, offer to research the answer online with them or find an organization that can provide accurate information.

If you suspect a child or adolescent in your care may be a victim of trafficking, connect them to people who can provide immediate and discreet assistance.

Educators should direct students to an appropriate resource, either to counseling services or a local organization connected with the school. A school counselor is better prepared to have explicit conversations with students and find the support they need.

“As a teacher, we have to be mindful that sometimes we are not equipped to handle such an issue, personally or professionally,” Dr. Scott says.

As an educator, you might bring up concerning behaviors you have noticed and gently suggest that the student sit down with the counselor.

Parents concerned about their children may also seek the school’s support. If you notice alarming behaviors in your child, such as coming home at odd times of the night, and discussions with them are not helping, reach out to your school’s counselor. Articulate those behaviors to the counselor, who can work with you to develop a plan of action for your child.

Begin these conversations with the children in your classroom or your home, and you will better prepare them to advocate against human trafficking and avoid being trafficked themselves.

If you or someone you know is a victim of human trafficking, call the National Human Trafficking Hotline now at 1-888-373-7888.

1 "Growing Awareness. Growing Impact. (PDF, 819 KB)," External link Polaris, December 18, 2018. Return to footnote reference

2 “Trafficking in Persons Report, June 2016 (PDF, 25.4 MB),” External link United States of America Department of State, December 20, 2018. Return to footnote reference

3 “The Typology of Modern Slavery,” External link Polaris, December 17, 2018. Return to footnote reference

4 “What Is Human Trafficking,” External link National Human Trafficking Hotline, December 17, 2018. Return to footnote reference

5 “Texas,” External link National Human Trafficking Hotline, December 17, 2018.